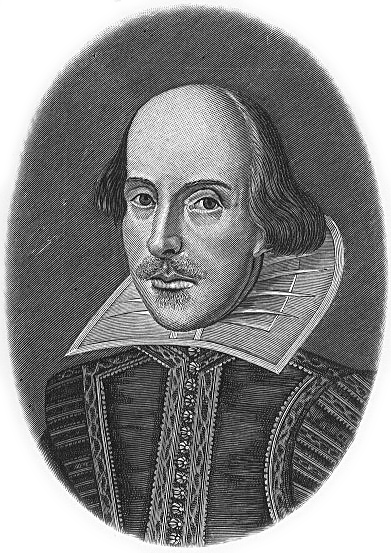

A few years ago, Martino Juvara, a retired schoolteacher from Ispica in the province of Ragusa, presented the theory that William Shakespeare had nothing to do with Stratford-upon-Avon but was in fact born in 1564 in Messina, Sicily, and given the name Guglielmo Crollalanza (’Falling Spear’). When still a boy, because of his father’s Calvinist leanings, the family was forced to flee to Verona, where they had relatives. Here the young Guglielmo stayed in a house belonging to a certain Othello (where a certain Desdemona had been killed), fell in love with a certain Juliet (who later committed suicide), and a few years later went on to England, where he changed his name to William Shakespeare to facilitate his acceptance into the new country. Juvara’s theory is largely based on a series of coincidences. Shakespeare mentions Sicily in five of his plays: Julius Caesar, Much Ado About Nothing, Antony and Cleopatra, A Comedy of Errors and A Winter’s Tale. His rich vocabulary would indicate a good knowledge of Italian, and he used many Sicilian proverbs in his works: ‘much ado about nothing’, for example, is a translation of the old proverbtantu schifiu ppi nenti, and ‘all’s well that ends well’ is si chiuriu ‘na porta e s’apriu un purticatu. What’s more, some of his biographers say Shakespeare had a foreign accent–though for a good actor that wouldn’t have been difficult to assume, if he wanted to give himself exotic appeal. So far, perhaps not surprisingly, this new idea about Shakespeare’s identity has met with widespread scepticism….

The 8th edition of Ellen Grady’s Blue Guide Sicily is out now.