Among the fragrant pines of the Adriatic island of Lokrum, a short boat ride away from the old town of Dubrovnik, stands a complex of buildings that began life as a votive chapel, founded by Richard the Lionheart in thanksgiving for his survival when he was shipwrecked here on his way home from the Crusades. That chapel expanded into a Benedictine monastery, which was dissolved by Napoleon and later transformed into a residence by Archduke Maximilian of Austria, younger brother of the emperor Franz Joseph. Maximilian used the building—and indeed the entire island—as a summer retreat, laying out ornamental gardens with glades of cypress and oleander. He came here with his beautiful young bride, Charlotte of Belgium. Entranced by the sea breeze and the scent of jasmine, he is said to have carved a love heart pierced with his own and his wife’s initials into the bark of one of Lokrum’s ilex trees. Local people were less enchanted. Their tongues wagged disapprovingly, calling what Maximilian had done to the old monastery an act of sacrilege and predicting dire consequences. Little did they know it, but their words were to turn prophetic…

The Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, born at Schönbrunn in 1832, was good-hearted and idealistic. After a career as Commander-in-Chief of the Austrian navy, he was given the title of Governor General of Lombardy, part of a strategy of Franz Joseph’s to make Austrian rule more popular in northern Italy. It didn’t work. Nationalist fever was running high and despite the fact that Maximilian was a just and benevolent overlord, Lombardy didn’t want him. Instead they looked to Napoleon III of France to liberate them. Austria went to war with France and lost Lombardy at the Battle of Solferino in 1859. Maximilian retreated to his castle on the bay of Trieste, and there he remained, until in 1863 he elected to accept an offer that had been made to him by a clerical minority faction in Mexico: to become their emperor. Maximilian was encouraged in this by Napoleon III. Franz Joseph was greatly troubled. He knew that this was pure political gerrymandering by France, whose ambitions in the New World were considerable. But Maximilian wanted to go. He was ambitious and he also had grand ideas, ideas that were very different from those of his reactionary brother. While Franz Joseph’s main concern was to preserve the status quo, Maximilian, equally fatally, wanted to ‘make a difference’.

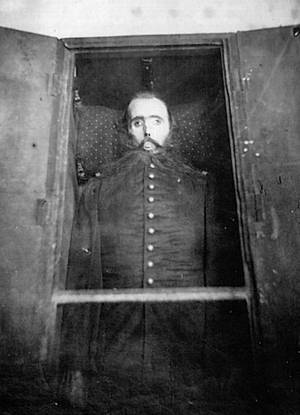

Maximilian did his best in Mexico, but he had as many enemies there as he had had in Italy. The country was in a state of guerilla war between the monarchist faction and the troops of Benito Juárez, whom the liberals supported and wanted as their president. Although Maximilian enjoyed the support of the conservatives at first, he alienated them by decreeing freedom of religion and by his instinctive personal sympathy for some of Juárez’s ideas. Pope Pius IX withdrew his support, and when the United States gave diplomatic recognition to Juárez, France withdrew likewise, being also under pressure at home from a rising Prussia. Maximilian was left friendless and unprotected. His wife Charlotte began to exhibit signs of paranoia. She returned to Europe to plead with both the pope and Napoleon, but after a series of hysterical and embarrassing scenes in the Vatican, she was sent to Trieste (Miramare castle) and kept there under house arrest by Maximilian’s family. Maximilian was captured by the republicans and sentenced to death. Despite many pleas for clemency, including one from Garibaldi, Juárez refused to relent. On the morning of 19th June 1867, Maximilian faced the firing squad.

Glimmering pearly white on the foreshore, just outside the city of Trieste and clearly visible from its waterfront and docks, stands the castle of Miramare. It was completed for Maximilian in 1860, and it is here, in 1866, that Charlotte took up residence when she returned from Mexico in her attempt to rally support for her beleaguered husband. Charlotte suffered a severe nervous breakdown after Maximilian’s death, from which she never fully recovered. She returned to Belgium, where she died in 1927. Miramare is now open to the public a museum.