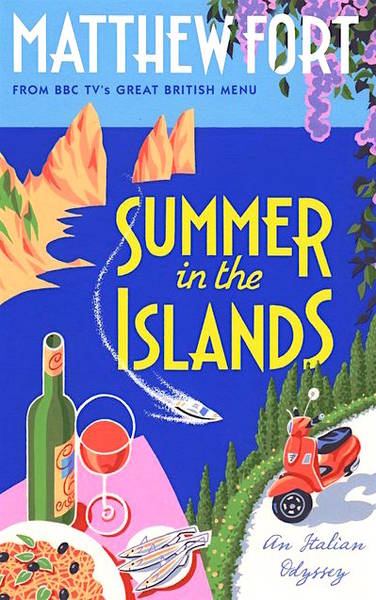

Matthew Fort: Summer in the Islands, An Italian Odyssey. Unbound Press, London, 2017.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman.

Matthew Fort, distinguished writer on food and all the conviviality that accompanies it, fell in love with Italy through its ice cream at the age of eleven. The relationship has lasted and has developed into a deep affection for Italy’s peoples and their traditions of fine local cooking. Having traversed the peninsula for Eating up Italy and explored Sicily in Sweet Honey, Bitter Lemons, he embarked, at the age of 67, on a leisurely six-month tour of all the islands off the Italian coast. It did not quite work out as planned: a ruptured Achilles tendon led to his abrupt return to England, but he eventually made it back to complete his visit to every Italian island, with Sardinia and Sicily included.

Italian restaurateurs love a genial and tubby figure who turns up to ask them what they cook best and then enjoys several courses of local specialities. Mr. Fort fits the bill brilliantly. From zuppetta di lenticchie usticese con totani from the fertile soil of Ustica to grigliata mista di suino in Alghero, Sardinia, and ricotta salata al forno, ‘salted ricotta that has been baked in the oven and sliced as thin as a communion wafer’, matched with a sweet Malvasia di Lipari in Salina off the coast of Sicily, he honours the cucina of wherever he turns up. Fort travels with Nicoletta, his trusty Vespa, and the pair are happy together chugging across the varied terrains thrown up by geology and volcanic eruptions (although of course Nicoletta cannot participate in the feasting). One lady who can is Fort’s daughter Lois, who joins him in Giglio and Giannutri, off Italy’s western coast. She is “curious, humorous, calm in the face of adversity [unlike Fort], cheerful and determined to enjoy each adventure to the full”, so they have happy times together and Fort is melancholy when she leaves. She will reappear in the final chapter when, on her first visit to Venice, they enjoy a beautifully served lunch at the Locanda Cipriani on Torcello. Other companions appear: Lisa, who disrupts Fort’s lazy lifestyle on Filicudi and Alicudi with two vast aluminium suitcases and a vigorous programme of walking and swimming.

I was worried at first that one island after another would prove monotonous; but each island is different. Some are crammed with holiday-makers and others with prisons (either abandoned or still functioning), so there is plenty of contrast and enough variety to keep the narrative going. Fort also knows enough history and literature to fill us in on Napoleon on Elba, for example, or the Dukes of Bronte, heirs of Nelson, in Sicily. There is a discursion on the ‘pagan’ Norman Douglas, whose memoir Old Calabria (1915) extols the wildness of Italy’s deep south; and frustration with a German film crew who have taken over Garibaldi’s farm on Caprera, depriving Fort of the chance to eat there. He sums up his ambivalent feelings about Garibaldi nonetheless.

I am one up on Fort in that I have a chance, on the tours I lead, to follow up the best restaurants my wife and I discover on our reconnoitring trips. So south of Naples I shall be re-visiting the Tre Olivi at Paestum (this time taking 30 people to lunch there) and the following day I will reacquaint myself with Ristorante Romantica near Teggiano, a small hilltop town where medieval frescoes will be opened up for us in the churches before we leave for the vast Certosa di San Lorenzo in the afternoon. There is no better way of honouring a restaurant than to bring one’s friends along for a second bite. I am sure that Matthew Fort would approve.

Charles Freeman is Historical Consultant to the Blue Guides and contributor to many Blue Guide Italy titles. For more on Italian food, try the Blue Guide Italy Food Companion.