“The Heartwarming Middle Ages” (Szívmelegítő Középkor) is the title of an appealing small exhibition running at the Budapest History Museum’s Buda Castle site until September.

The forerunner of the ceramic stove is thought to have originated in Alpine Switzerland sometime in the early Middle Ages, when simple clay pots were built into house chimneys to increase the surface area that could be made to give out warmth. In Óbuda, Budapest’s District III, excavations at Roman Aquincum have revealed rows of hollow bricks placed between interior walls to circulate warm air from the hypocaust beneath. This sophisticated early radiation technology had been forgotten after the collapse of the Roman Empire and—until the Swiss hit upon the clay pots idea—people heated their living spaces with smoky open fires, creating a constant risk of conflagration (not to mention a carcinogenic atmosphere). The Swiss innovation was almost as great a leap forward as the invention of the internal combustion engine in much later times.

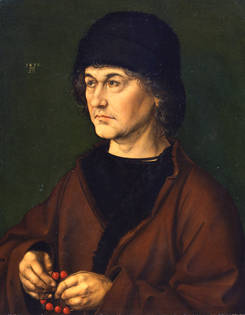

The exhibition begins with a selection of images evoking the winter chill of northern climes. Among them is an etching by Dürer (c. 1498, from the Prints and Drawings collection of the Hungarian Museum of Fine Arts) entitled The Philosopher’s Dream, showing a savant fast asleep beside a tile stove, dreaming of a visitation by a naked Venus. The stove he sleeps beside looks much like the tile-clad stoves that are still a familiar feature of Central European interiors.

Much as the first automobiles preserved the bodywork of the horse-drawn carriage, the first stoves were clad in tiles that retained the concave shape of the original earthen pots. Later, tile shapes became more elaborate and inventive. The exhibition traces this development. Ceramic is not perishable and in Buda—where so much has been destroyed—the tile survivals are some of the finest and most poignant reminders of the glory that once presided here. The material exhibited in this show comes from the rich collection of the Budapest History Museum as well as from further afield, in Hungary as well as Slovakia and Transylvania. The earliest tile finds are from the 12th century, although the technology probably predates this by some 300 years. It was a democratic technology: fired earth is not a luxury material and its application made warmth available to princes, prelates and peasants alike.

We know that underfloor heating returned to Hungary: the palace of Charles I (r. 1310–42) in Visegrád had it, while the upper floor was heated by a stove clad in cup-shaped tiles. Charles’ successor, Louis I (r. 1342–82) had stoves clad in flat, decorated tiles. By the mid-15th century foreign (probably Austrian) craftsmen were supplying the Hungarian court with high-quality, sophisticatedly decorated ceramic ware. Motifs include floral designs, bunches of grapes, knights in armour, biblical and other Christian motifs, heraldic devices, and royal personages. Fine examples on show include a Lamb of the Resurrection in green lead glaze from Banská Bystrica and a yellow-lead glazed crest of King Sigismund (d. 1437) with fine mantling and two badges of the Order of the Dragon (which Sigismund founded to combat Ottoman expansion; Vlad Dracul, father of the Impaler, is said to have taken his name from the Order). The image of a siren saucily parting her fishy tail is also popular. The exhibition has three of these, all from the collection of the Budapest History Museum (protoype of the Starbucks logo). There is also a splendid polychrome tile depicting King Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–90) seated in majesty. King Matthias, under whom Buda enjoyed a great flowering, seems to have been adept at using his own image as a brand.

By means of its decoration, the stove became at once a means of heating a room and also a vehicle for imparting information about the householder’s lineage, prestige and religious faith, as well as entertainment (stories of chivalry, popular legends and fables), much like a painting or a tapestry. The final part of the exhibition shows how the royal lead in stove manufacture was quickly imitated down the social scale. Soon bishops and barons and well-to-do burghers wanted cosy, smoke-free living spaces, and to achieve them they copied both the technique and the tile designs. Like coins, medals or seals, made from moulds and dies, stove tiles could be mass-produced, allowing identical images to proliferate. As the exhibition points out, ceramic manufacture was far in advance of the printing press in its ability to standardise the conceptual vocabulary of the populace. The last tiles in the show are secular in their subject matter: we see an irate wife belabouring her husband, a young man with a tankard of beer, and a pair of lovers in flagrante.Green-glaze stove tile showing a pair of lovers (c. 1500. Stredlovenské Museum, Banská Bystrica).

The final room is provided with a video screen showing a crackling fire. You have to work hard to imagine its warmth, though. To protect the fragile glazes, temperatures throughout the exhibition are kept low. Bring a light sweater!